This is my third year returning to the National Park Sharr in the summer. Each time, I am picked up by a friend of GAIA at the foothills of the National Park close by the colossal walls of Narciss, a proud relic of the Yugoslav period. As the car climbs up the roughly 1700 meters in altitude, I pass vast pastureland, small restaurants lining up along the roadside, and ever-expanding pockets of luxurious homes of the vacation zone. Overshadowed by the massive mountain ridge of the National Park the weekend-zone consists of construction sites for hotels and holiday cabins. It gulps up land like the very hungry caterpillar to make room for the very rich living in Kosovo. Just that it won’t have a beautiful ending. Each year, its concrete foundations stretches deeper into the foothills of the mountainous landscape. The rate and style of the constructions may very well qualify as “turbo-development” in an environment that should be protected.

Sharr National Park is perhaps one of Balkans most underestimated locations for outdoor activities and natural excursions. It was founded in 1986 and has been divided into three differently graduated protected zones since then. There are only a few documentations on its biodiversity and species available to testify for the rich biodiversity of the mountain. The lack of data and its inaccessibility to the wider public definitely explains one part of the general indifference that has been paid towards Sharr. Although locals and tourists make regular use of the landscape and its skiing facilities during winter periods, the mountain receives little attention during summer months.

Throughout warmer months, it is normal to see children claiming the asphalt road in front of Motel Bucan with miniature quads, mopeds or other motorized vehicles to send seismic shockwaves through the foundations of the massive. I have also come to terms with the reality that most visitors simply enjoy the ride up the caveated mountain road protected by the tinted windows of their SUVs, snap a selfie and hurdle back down to their weekend escapes. It would be unfair, however, to moralize their behavior since the infrastructure within the NP fails to inform them about the national park and what it stands for. The park generally lacks basic facilities such as a visitor center, any information about the natural environment or hiking trails, trail demarcations, and a guide of how to behave in protected areas. In the end, Sharr remains relatively underdeveloped, untouched, yet also under-researched which provides for an ideal environment where anyone can avail themselves for whatever their needs are. Be it dumping their domestic garbage, mining rocks from the protected areas, and, last but not least, stealing its water.

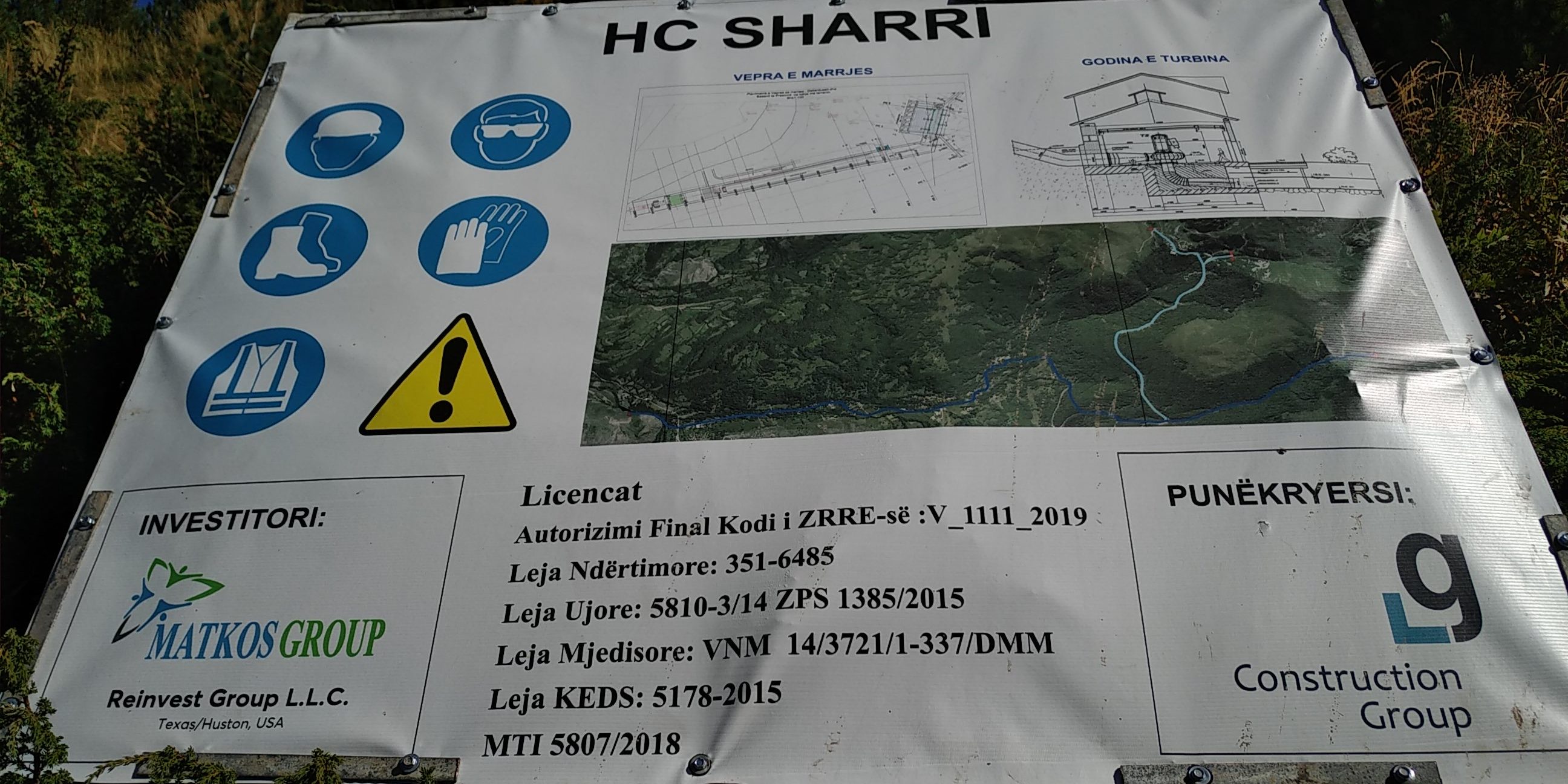

The turbo-development for hydropower in the region has reached the national park’s infertile ground to privatize free flowing water streams. With an environmental consent issued by the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning in their pocket, MATKO’s group, a building company based in Prishtina, commenced digging up two streams in NP, Durlov Potok and Berevački Potok, this month. Their permissions dates back to 2013 and has been prolonged twice.

The construction work has not come without direct opposition by local people who depend on the Lepenac/Lepenc river and fear for the environmental impacts of the small-scale hydropower plants. Two organized protests took place in September, uniting members from different communities and ages in the fight against the destruction of Sharr’s precarious natural goods.

Their worries are not unjustified. Research on small scale hydro-power plants in the region sponsored by Riverwatch persistently refutes their economic and environmental benefits.

“Small scale hydropower makes neither environmental nor economic sense. It causes immense damage to nature and inflames social conflict whilst providing a disproportionately tiny amount of electricity of a country’s overall energy needs.” (Riverwatch and Euronature, 2018)

The construction of these two mini-hydropower plants boils down to an environmental justice and a human rights issue. According to Eco-Masterplan for Balkan Region, the river systems in the national park Sharr fall under the category of “No-Go Rivers” which makes them a high priority protected area that must be preserved from human intervention and infrastructure projects (2018, p. 35). These areas are foremostly to be protected for their ecological value and the location they are in, namely protected areas. In the case of Kosovo more generally, water is a scarce resource that is already put under stress by prolonged droughts in the summer months. Sharr NP in particular, comprises of limited and small scale streams and among these, the Lepenac/Lepenc river, is paramount to the well-being of people’s livelihoods that are fed by the stream in Brezovica/Brezovicë and Štrpce/Shtërpcë, according to Luan Shllaku, environmentalist and executive director of KFOS. Any intervention bears with it long-term environmental costs that accumulate from the construction phase throughout the maintenance of these plants. I genuinely ask you: Can the plants’ expected overall capacity of about 5.5 MW realistically contribute to the needed one-fifth produced by renewables? And how can this poor equation justify the destruction of the formally observed natural habitat of the endangered Balkan Lynx?

The promotion and protection of the natural resources of the national park is also a human rights issue. The intactness of the ecosystem of the river is a prerequisite to the exercise of the fundamental human right to life and health. The right to water declares everyone’s entitlement to access to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. Underpinning these linkages are procedural rights such as the accessibility of environmental information to the public for public participation in environmental decision-making and to ensure access to effective remedies. Environmental data on the potential impact of these two powerplants as well as other HPPS in the municipality of Štrpce/Shtërpcë never appropriately reached the intended public, namely those living in Brezovica/Brezovicë and Štrpce/Shtërpcë who will be directly impacted by any obstruction of the streams. Instead, it was held in in the year of, uprooting the legal baseline of the construction permits issued by the ministries and the local municipality of Štrpce/Shtërpcë.

The lacking transparency of how the permit has been obtained, and to what degree procedural law on EIA has been followed, leaves me with the assumption that someone makes extra effort in hiding the political circumstances of the whole project. Meanwhile, residents of Brezovica/Brezovicë, Štrpce/Shtërpcë and Jažince /Jazhincë are already subject to irregular access to water due to the constructions in the NP, as has been told to me by Iva Bućan who is the owner of the Motel Bućan in the Brezovica Ski resort.

The struggle for Sharr continues.

Having been part of several initiatives and youth gatherings in Sharr and Prishtina, I can feel the flickering flame of change. People care about their natural heritage when its well-being is directly connected to their own. This is fair enough, because our very own security is deeply embedded in our natural environment’s provision for it. We do not feed off it or live with nature. When natural resources are scarce, we logically protect them, and do not put them out for sale. Suggesting the contrary, as was done by a representative of Ministry of Spatial Planning at the ending ceremony of the KSDW 19, provides us with another example of climate policies saturated with full-blown cognitive dissonance.

I am leaving the mountain for now with the intention to come back and see how locals and the young people, which I have met this September, join to protect their natural heritage against the façade of “green energy.” In less than two weeks, Kosovo ‘s parliamentary elections are to be held. Take this opportunity to inquire about the environmental agenda of your representatives and how they plan to disseminate environmental information that enables you to participate in decision-making processes. Get informed about their promised action against the climate crisis and how they seek to reform Kosovo’s energy sector and address the inaccessibility of drinking water for 25% of Kosovo’s population. Cast your vote and demand just environmental policies for everyone and bolder climate actions. The longer it takes to solve Kosovo’s reliance on coal energy, the more costly they will become. And we, the everyday people, have to sacrifice our health for it.

I will do my part. I am leaving to Austria to cast my vote as well. My suggestions to you are also applicable to me. I too must hold my politicians to account for their policy promises because the climate crisis does not follow our meticulously constructed nation-state boundaries.

Rosa Hergan, European Solidarity Corps volunteer